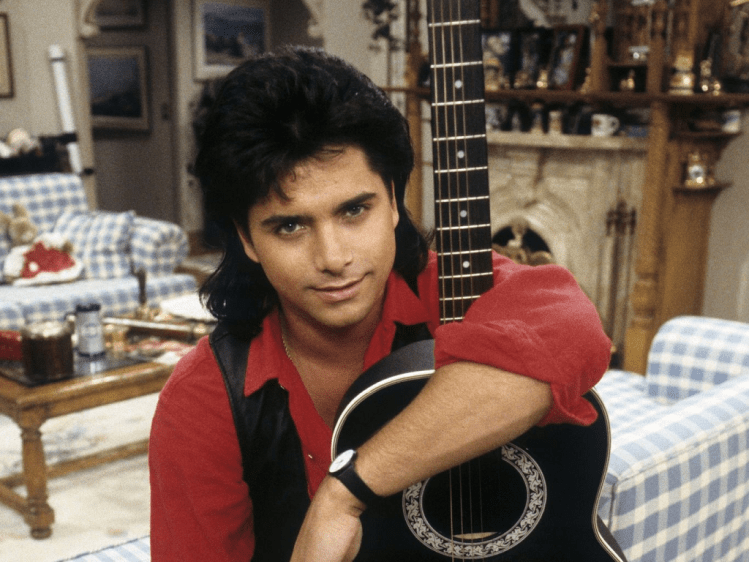

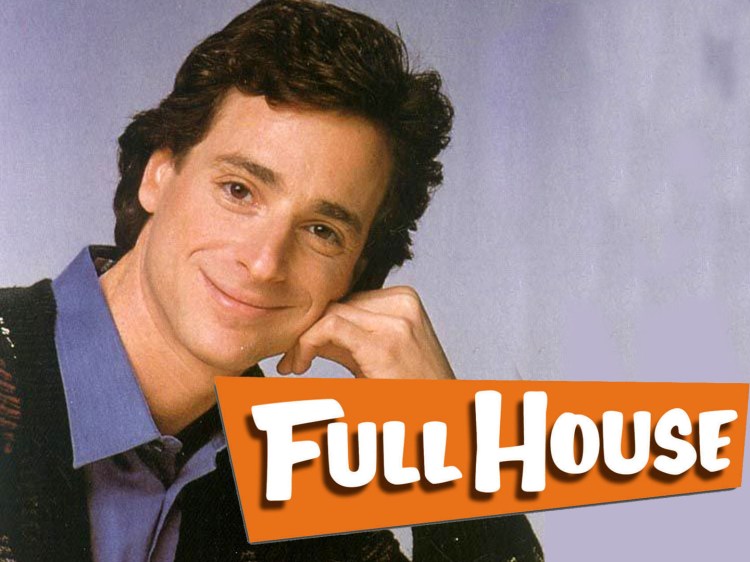

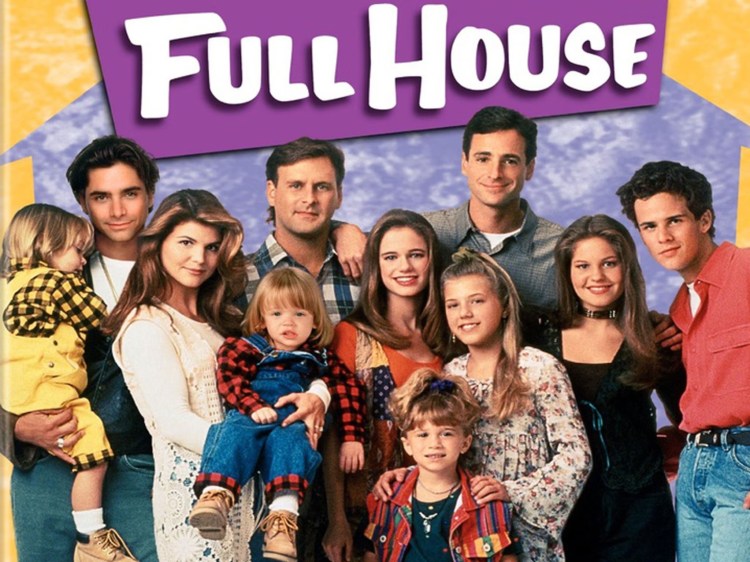

Welcome to this podcast installment of my look at the classic family sitcom Full House. Click the play button below to listen.

DISCLAIMER: Some material for this post was derived from various public sources on the Web.

An in-depth look at popular television shows, TV movies, miniseries, and the people behind them

Welcome to this podcast installment of my look at the classic family sitcom Full House. Click the play button below to listen.

DISCLAIMER: Some material for this post was derived from various public sources on the Web.

Welcome to this podcast installment of my look at the classic family sitcom Full House. Click the play button below to listen.

DISCLAIMER: Some material for this post was derived from various public sources on the Web.

Welcome to this podcast installment of my look at the classic family sitcom Full House. Click the play button below to listen.

DISCLAIMER: Some material for this post was derived from various public sources on the Web.

Welcome to this podcast installment of my look at the classic family sitcom Full House. Click the play button below to listen.

DISCLAIMER: Some material for this post was derived from various public sources on the Web.

Welcome to this podcast installment of my look at the classic family sitcom Full House. Click the play button below to listen.

DISCLAIMER: Some material for this post was derived from various public sources on the Web.

Welcome to this podcast installment of my look at the classic family sitcom Full House. Click the play button below to listen.

DISCLAIMER: Some material for this post was derived from various public sources on the Web.

A lot happened in the year 1987, including the debut of a family-friendly TV sitcom set in San Francisco. The name of the show was Full House, and we’ll be doing a deep dive into this popular comedy over the coming weeks.

But first, to get a sense of the times and trends that helped shape this series, here’s a notable obituary from 1987 — Woody Herman.

Woody Herman was an American jazz clarinetist, saxophonist, singer, and big band leader. Leading groups called “The Herd”, Herman came to prominence in the late 1930s and was active until his death in 1987. His bands often played music that was cutting edge and experimental; their recordings received numerous Grammy nominations.

As a child he worked as a singer and tap-dancer in vaudeville, then started to play the clarinet and saxophone by age 12. In 1931 he met Charlotte Neste, an aspiring actress; the couple married on September 27, 1936. Woody Herman joined the Tom Gerun band and his first recorded vocals were “Lonesome Me” and “My Heart’s at Ease”. Herman also performed with the Harry Sosnick orchestra, Gus Arnheim and Isham Jones. Isham Jones wrote many popular songs, including “It Had to Be You” and at some point was tiring of the demands of leading a band. Jones wanted to live off the residuals of his songs; Herman saw the chance to lead his former band and eventually acquired the remains of the orchestra after Jones’ retirement.

Herman’s first band became known for its orchestrations of the blues, and was sometimes billed as “The Band That Plays The Blues”. This band recorded for the Decca label, at first serving as a cover band, doing songs by other Decca artists. The first song recorded was “Wintertime Dreams” on November 6, 1936. In January 1937, George T. Simon ended a review of the band with the words: “This Herman outfit bears watching; not only because it’s fun listening to in its present stages, but also because it’s bound to reach even greater stages.” After two and a half years on the label, the band had its first hit, “Woodchopper’s Ball” recorded in 1939. Herman remembered that “Woodchopper’s Ball” started out slowly. “[I]t was really a sleeper. But Decca kept re-releasing it, and over a period of three or four years it became a hit. Eventually it sold more than five million copies—the biggest hit I ever had.” In January 1942, Herman would have his highest rated single, singing Harold Arlen’s “Blues in the Night” backed by his orchestra. Other hits for the band include “Blue Flame” and “Do Nothin’ Till You Hear from Me”. Musicians and arrangers that stood out included Cappy Lewis on trumpet and saxophonist/arranger Deane Kincaide. “The Golden Wedding” (1941), arranged by James “Jiggs” Noble, featured an extended drum solo by Frankie Carlson.

The trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie wrote three arrangements for Herman, “Woody’n You”, “Swing Shift” and “Down Under”. These were arranged in 1942. “Woody’n You” was not used at the time. “Down Under” was recorded July 24, 1942. Herman’s commissioning Gillespie to write arrangements for the band and hiring Ralph Burns as a staff arranger heralded a change in the style of music the band was playing.

In February 1945, the band started a contract with Columbia Records. Herman liked what drew many artists to Columbia, Liederkranz Hall, at the time the best recording venue in New York City. The first side Herman recorded was “Laura”, the theme song of the 1944 movie. Herman’s version was so successful that it prevented Columbia from releasing the arrangement that Harry James had recorded days earlier. The Columbia contract coincided with a change in the band’s repertoire. The 1944 group, which he called the First Herd, was known for its progressive jazz. The First Herd’s music was heavily influenced by Duke Ellington and Count Basie. Its lively, swinging arrangements, combining bop themes with swing rhythm parts, were greatly admired. As of February 1945, the personnel included Sonny Berman, Pete Candoli, Bill Harris, Flip Phillips, Billy Bauer, Ralph Burns, and Davey Tough. On February 26, 1945, in New York City, the Woody Herman band recorded “Caldonia”.

Neal Hefti and Ralph Burns collaborated on the arrangement of “Caldonia” that the Herman band used. “Ralph caught Louis Jordan [singing “Caldonia”] in an act and wrote the opening twelve bars and the eight-bar tag.” “But the most amazing thing on the record was a soaring eight bar passage by trumpets near the end.” These eight measures have wrongly been attributed to a Gillespie solo, but were in fact originally written by Neal Hefti. George T. Simon compares Hefti with Gillespie in a 1944 review for Metronome magazine saying, “Like Dizzy […], Hefti has an abundance of good ideas, with which he has aided Ralph Burns immensely”.

In 1946, the band won DownBeat, Metronome, Billboard and Esquire polls for best band, nominated by their peers in the big band business.

Classical composer Igor Stravinsky wrote the Ebony Concerto, one in a series of compositions commissioned by Herman with solo clarinet, for this band in 1945. Herman recorded the work at Belock Recording Studio in Bayside, New York. Herman called it a “very delicate and a very sad piece.” Stravinsky felt that the jazz musicians would have a hard time with the various time signatures. Saxophonist Flip Philips said: “During the rehearsal […] there was a passage I had to play there and I was playing it soft, and Stravinsky said ‘Play it, here I am!’ and I blew it louder and he threw me a kiss!” Stravinsky observed the massive amount of smoking at the recording session: “the atmosphere looked like Pernod clouded by water.” Ebony Concerto was performed live by the Herman band on March 25, 1946, at Carnegie Hall.

Despite the Carnegie Hall success and other triumphs, Herman was forced to disband the orchestra in 1946 at the height of its success. This was his only financially successful band; he left it to spend more time with his wife and family. During this time, he and his family had just moved into the former Hollywood home of Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall. One reason Herman may have disbanded was his wife Charlotte’s growing alcoholism and pill addiction. Charlotte Herman joined Alcoholics Anonymous and gave up everything she was addicted to. Woody said, laughing: “I went to an AA meeting with Charlotte and my old band was sitting there.” Many critics cite December 1946 as the actual date the big-band era ended, when seven other bands, in addition to Herman’s, dissolved.

In 1947, Herman organized the Second Herd. This band was also known as “The Four Brothers Band”. This derives from the song recorded December 27, 1947, for Columbia Records, “Four Brothers”, written by Jimmy Giuffre, featuring the saxophone section of Zoot Sims, Serge Chaloff, Herbie Steward, and Stan Getz. The other musicians of this band included Al Cohn, Gene Ammons, Lou Levy, Oscar Pettiford, Terry Gibbs, and Shelly Manne. Among this band’s hits were “Early Autumn”, and “The Goof and I”. The band was popular enough that they went to Hollywood in the mid-1940s. Herman and his band appear in the movie New Orleans (1947) with Billie Holiday and Louis Armstrong.

In 1947, Herman was Emcee and also played at the third Cavalcade of Jazz concert held at Wrigley Field in Los Angeles which was produced by Leon Hefflin, Sr. on September 7, 1947. The Valdez Orchestra, The Blenders, T-Bone Walker, Slim Gaillard, The Honeydrippers, Johnny Otis and his Orchestra, Sarah Vaughn and the Three Blazers also performed that same day.

Herman’s other bands include the Third Herd (1950–56) and various later editions during the 1960s. In the 1950s, the Third Herd successfully toured Europe. He was known for hiring the best young musicians and using their arrangements. In the early and mid 1960s, Herman fronted a Herd featuring Michael Moore, drummer Jake Hanna, tenor saxophonist Sal Nistico, trombonists Phil Wilson and Henry Southall and trumpeters like Bill Chase, Paul Fontaine and Duško Gojković. By 1968, the Herman library came to be heavily influenced by rock and roll. He was also known to feature brass and woodwind instruments rarely associated with jazz, such as the bassoon, oboe or French horn.

In concert, as the evening wore on and the crowd started dissipating, Herman would often leave the stage and let the band continue the last set on its own; but Terry Gibbs confirmed that the band never sounded the same without Herman being present.

In the early 1970s, he toured frequently and began to work more in jazz education, offering workshops and taking on younger sidemen. For this reason, he got the nickname Road Father and the bands were known as the “Young Thundering Herds.” In January 1973, Herman was one of the featured halftime performers at Super Bowl VII. In 1974, Woody Herman’s band appeared without their leader for Frank Sinatra’s television special The Main Event and album The Main Event – Live. Both were recorded mainly on October 13, 1974, at Madison Square Garden in New York City. On November 20, 1976, a reconstituted Woody Herman band played at Carnegie Hall in New York City, celebrating Herman’s fortieth anniversary as a bandleader.

By the 1980s, Herman had returned to more straight-ahead jazz but augmented with rock and fusion. Herman signed a recording contract with Concord Records around 1980. In 1981, John S. Wilson reviewed one of Herman’s first Concord recordings Woody Herman Presents a Concord Jam, Vol. I. Wilson’s review says that the recording presents a band that is less frenetic than his bands from the forties to the seventies. Instead, it takes the listener back to the relaxed style of Herman’s first band of the thirties that recorded for Decca.

Herman continued to perform into the 1980s, after the death of his wife and with his health in decline, chiefly to pay back taxes that were owed because of his business manager’s bookkeeping in the 1960s. Herman owed the IRS millions of dollars and was in danger of eviction from his home. With this added stress, Herman still kept performing. In a December 5, 1985, review of the band at the Blue Note jazz club for The New York Times, John S. Wilson pointed out: “In a one-hour set, Mr. Herman is able to show off his latest batch of young stars—the baritone saxophonist Mike Brignola, the bassist Bill Moring, the pianist Brad Williams, the trumpeter Ron Stout—and to remind listeners that one of his own basic charms is the dry humor with which he shouts the blues.” Wilson also spoke about arrangements by Bill Holman and John Fedchock for special attention. Wilson spoke of the continuing influence of Duke Ellington on Woody Herman bands from the 1940s to the 1980s. Before Woody Herman died in 1987 he delegated most of his duties to leader of the reed section, Frank Tiberi. Tiberi leads the current version of the Woody Herman orchestra. Tiberi said at the time of Herman’s death that he would not change the band’s repertoire or library. Herman died on October 29, 1987, and had a Catholic funeral on November 2 at St. Victor’s in West Hollywood, California. He is interred in a niche in the columbarium behind the Cathedral Mausoleum in the Hollywood Forever Cemetery.

Awards won by the Woody Herman orchestras with major publications: “Voted best swing band in 1945 DownBeat poll; Silver Award by critics in 1946 and 1947 Esquire polls; won Metronome poll, band division, 1946 and 1953.

A documentary film titled Woody Herman: Blue Flame – Portrait of a Jazz Legend was released on DVD in late 2012 by the jazz documentary filmmaker Graham Carter, owner of Jazzed Media, to salute Herman and his centenary in May 2013.

A lot happened in the year 1987, including the debut of a family-friendly TV sitcom set in San Francisco. The name of the show was Full House, and we’ll be doing a deep dive into this popular comedy over the coming weeks.

But first, to get a sense of the times and trends that helped shape this series, here’s a notable obituary from 1987 — Woody Hayes.

Woody Hayes was an American football player and coach. He served as the head coach at Denison University (1946–1948), Miami University in Oxford, Ohio (1949–1950), and Ohio State University (1951–1978), compiling a career college football record of 238 wins, 72 losses, and 10 ties. He was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame as a coach in 1983.

During his 28 seasons as the head coach of the Ohio State Buckeyes football program, Hayes’s teams were selected five times as national champions, from various pollsters, including three (1954, 1957, 1968) from major wire-service: AP Poll and Coaches’ Poll. Additionally, his Buckeye teams captured 13 Big Ten Conference titles, and amassed a record of 205–61–10.

Over the last decade of his coaching tenure at Ohio State, Hayes’s Buckeye squads faced off in a fierce rivalry against the Michigan Wolverines coached by Bo Schembechler, a former player under and assistant coach to Hayes. During that stretch in the Michigan–Ohio State football rivalry, dubbed “The Ten Year War”, Hayes and Schembechler’s teams won or shared the Big Ten Conference crown every season and usually each placed in the national rankings.

Upon returning to Denison in 1946, Hayes had a hard first year, winning only 2 games, over Capital and the season finale against Wittenberg. However, that victory sparked a 19-game winning streak, a surge that propelled him into the head coaching position at Miami University. Miami is recognized as the “Cradle of Coaches” because of its history of outstanding coaches starting their careers there, such as Paul Brown, Ara Parseghian, Weeb Ewbank, Bill Mallory, Sid Gillman, Randy Walker, and Bo Schembechler. After the 1947 season, Gillman moved down the road to coach at the University of Cincinnati, which was then Miami’s chief rival. Hayes and Gillman maintained a sparkling feud between themselves, combining mutual distaste for the other’s coaching style, and because they were in recruiting competition in the same general area.

In his second year with the Miami Redskins, Hayes led the 1950 team to an appearance in the Salad Bowl, where they defeated Arizona State. That success led him to accept the Ohio State head coaching position on February 18, 1951, in a controversial decision after the university rejected the applications of other more well-known coaches, including former Buckeyes’ head coach Paul Brown, incumbent Buckeye assistant Harry Strobel, and Missouri head coach Don Faurot.

As head coach of the Ohio State Buckeyes, Hayes led his teams to a 205–61–10 record (.761), including three consensus national championships (1954, 1957, and 1968), two other non-consensus national titles (1961 and 1970), 13 Big Ten conference championships, and eight Rose Bowl appearances. Hayes was a three-time winner of The College Football Coach of the Year Award, now known as the Paul “Bear” Bryant Award, and was “the subject of more varied and colorful anecdotal material than any other coach past or present, including fabled Knute Rockne”, according to biographer Jerry Brondfield.

Hayes’ basic coaching philosophy was that “nobody could win football games unless they regarded the game positively and would agree to pay the price that success demands of a team.” His conservative style of football (especially on offense) was often described as “three yards and a cloud of dust”—in other words, a “crunching, frontal assault of muscle against muscle, bone upon bone, will against will.” The basic, bread-and-butter play in Hayes’ playbook was a fullback off-guard run or a tailback off tackle play. Hayes was often quoted as saying “only three things can happen when you pass (a completion, an incompletion, and an interception) and two of them are bad.”

In spite of this apparent willingness to avoid change, Hayes became one of the first major college head coaches to recruit African-American players, including Jim Parker, who played both offensive and defensive tackle on Hayes’ first national championship team in 1954. While Hayes was not the first to recruit African-Americans to Ohio State, he was the first to recruit and start African-Americans in large numbers there and to hire African-American assistant coaches.

Another Hayes recruit, Archie Griffin, was the only two-time Heisman Trophy winner in seven decades of selections. Altogether, Hayes had 58 players earn All-America honors under his tutelage. Many notable football coaches, such as Lou Holtz, Bill Arnsparger, Bill Mallory, Dick Crum, Bo Schembechler, Doyt Perry, Ara Parseghian and Woody’s successor, Earle Bruce, served as his assistants at various times.

Hayes often used illustrations from historical events to make a point in his coaching and teaching. When Hayes was first hired to be the head coach at Ohio State, he was also made a “full professor of physical education”, having earned an M.A. degree in educational administration from Ohio State in 1948. The classes he taught were usually full, and he was called “Professor Hayes” by students. Hayes also taught mandatory English and vocabulary classes to his freshman football players. One of his students was a basketball player named Bobby Knight, who later became a legendary basketball coach.

During his time at Ohio State, Hayes’ relationships with students and faculty members were particularly good. Even those members of the faculty who believed that the role of intercollegiate athletics was growing out of control respected Hayes personally for his commitment to academics, the standards of integrity with which he ran his program, and the genuine enthusiasm he brought to his hobby as an amateur historian. Hayes often ate lunch or dinner at the university’s faculty club, interacting with faculty and administrators.

As a coach and an educator, Hayes was one of the first to use the motion picture as a teaching and learning tool. He was also memorable in that he could often be seen walking across campus, taking the time to visit with students. When talking to young people, Hayes treated all with respect, without regard to race or socio-economic class. This behavior was helpful to Ohio State in quelling the violence and damage from anti-war demonstrations that other college campuses suffered in the late 1960s and early 1970s. He took the time to communicate with student leaders. Then-team quarterback Rex Kern said, “Woody was out there on the Oval with the protesters, and he’d grab a bullhorn and tell the students to express their beliefs but not be destructive. He believed in Nixon, and he believed in the Establishment, but he wasn’t afraid to talk to the students. He wanted to stay close to the action.” Hayes was considered one of the few authority figures that students then had respect for. His enthusiasm for coaching and winning was such that many across the nation consider the following maxim to be true: “What Vince Lombardi was to professional football, Woody Hayes was to college football.”

During his tenure at Ohio State, Hayes joked that he considered himself to be Notre Dame’s best recruiter because if he could not convince a recruit to come to Ohio State instead of Michigan he would try to steer the recruit to Notre Dame, whom Ohio State did not play. While Hayes’ public stance was that he refused to play Notre Dame because he was afraid of polarizing the Catholic population in Ohio, Notre Dame’s long-time athletic director Edward “Moose” Krause said that Hayes had told him that Hayes liked having Michigan as the only tough game on the Ohio State schedule and that having the Buckeyes play Notre Dame would detract from that. Despite Hayes’ apparent fear of playing more than one “tough” game a year, Ohio State still managed to schedule regular-season games with Nebraska, Washington, Southern California, UCLA, and Oklahoma during his tenure.

After losses or ties, Hayes conducted locker room interviews while naked. A journalist from his tenure noted, “He was an ugly guy so it would clear the locker room out pretty fast.”

On December 29, 1978, the Buckeyes played in the Gator Bowl against Clemson. Late in the fourth quarter, Clemson was leading Ohio State 17–15. Freshman quarterback Art Schlichter managed to get Ohio State into field goal range. On third and 5 at the Clemson 24-yard line with 2:30 left and the clock running, Hayes called a pass rather than a run, because Schlichter was having a great game up to that point. Schlichter’s next pass was intercepted by Clemson nose guard Charlie Bauman, who returned it toward the Ohio State sideline, where he was run out of bounds. After Bauman stood up facing the OSU sideline Hayes punched him in the throat, triggering a bench-clearing brawl. Hayes stormed onto the field and was abusive towards the referee. When one of Hayes’ own players, offensive lineman Ken Fritz, tried to intervene, Hayes turned on him and had to be restrained by defensive coordinator George Hill. The Buckeyes were assessed two 15-yard unsportsmanlike conduct penalties for Hayes’ attack on Bauman and his abuse towards the referee. Bauman was not injured by Hayes’ punch and shrugged the incident off. Even though the game was being televised by ABC, neither announcer Keith Jackson nor co-announcer Ara Parseghian saw or commented about the punch. (At the time, all non-press box cameras were operated remotely from another site, and Jackson allegedly did not actually witness the punch, his view of the sidelines being blocked by the upper tier of the stadium).

After the game, Ohio State Athletic Director Hugh Hindman, who had played for Hayes at Miami University and had been an assistant under him for seven years, privately confronted Hayes in the Buckeye locker room. He said that he intended to tell school president Harold Enarson about what happened, and strongly implied that Hayes had coached his last game at Ohio State. After a heated exchange, Hindman said that he then offered Hayes a chance to resign, but Hayes refused, saying, “That would make it too easy for you. You had better go ahead and fire me.” Hindman then met with Enarson at a country club near Jacksonville, and the two agreed that Hayes had to go.

The next morning, Hindman told Hayes that he had been fired. A press conference was held at the hotel where the team had been staying. The team returned to Columbus around noon, and Hayes left the airport in a police car. Regarding Hayes’ dismissal, Enarson said that “there isn’t a university or athletic conference in this country that would permit a coach to physically assault a college athlete.” After the incident, Hayes reflected on his career by saying, “Nobody despises to lose more than I do. That’s got me into trouble over the years, but it also made a man of mediocre ability into a pretty good coach.” About two months after the incident, Hayes called Bauman in his dorm room, but did not apologize for his previous attack on him. Earle Bruce succeeded Hayes as Ohio State’s head coach.

Many years later, Leonard Downie, Jr., former executive editor of The Washington Post and student journalist at Ohio State, said he regretted not reporting an incident in the 1960s where Hayes instructed a player to take off his helmet and then hit him in the head.

According to the 1994 HBO documentary American Coaches: Men of Vision and Victory, Hindman had placed Hayes on notice at the beginning of the 1978 season, not just for the swing at the ABC cameraman during the 1977 Michigan game, but also for hitting a player during practice. In his 1989 autobiography, Michigan’s Bo Schembechler wrote that he believed Hayes, who was diabetic and may have had a high blood sugar level, didn’t believe he struck Bauman. Schembechler also pointed out that Hayes had maintained that all he was trying to do was grab the ball away.

A lot happened in the year 1987, including the debut of a family-friendly TV sitcom set in San Francisco. The name of the show was Full House, and we’ll be doing a deep dive into this popular comedy over the coming weeks.

But first, to get a sense of the times and trends that helped shape this series, here’s a notable obituary from 1987 — William Casey.

William Casey was the Director of Central Intelligence from 1981 to 1987. In this capacity he oversaw the entire United States Intelligence Community and personally directed the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA).

Following his admission to the bar, he was a partner in the New York–based Buckner, Casey, Doran and Siegel from 1938 to 1942. Concurrently, as chairman of the board of editors of the Research Institute of America (1938–1949), Casey initially conceptualized the tax shelter and “explained to businessmen how little they need[ed] to do in order to stay on the right side of New Deal regulatory legislation.”

During World War II, he worked for the Office of Strategic Services, where he became head of its Secret Intelligence Branch in Europe. He served in the United States Naval Reserve until December 1944 before remaining in his OSS position as a civilian until his resignation in September 1945; as an officer, he attained the rank of lieutenant and was awarded the Bronze Star Medal for meritorious achievement.

Following the dissolution of the OSS in September 1945, Casey returned to his legal and business ventures. After serving as a special counsel to the United States Senate (1947–1948) and associate general counsel to the Point Four Program (1948), Casey founded the Institute for Business Planning in 1950; there, he amassed much of his early wealth (compounded by investments) by writing early data-driven publications on business law. He was a lecturer in tax law at the New York University School of Law from 1948 to 1962. From 1957 to 1971, he was a partner at Hall, Casey, Dickler & Howley, a New York corporate law firm, under the auspices of founding partner and prominent Republican politician Leonard W. Hall. He ran as a Republican for New York’s 3rd congressional district in 1966, but was defeated in the primary by former Congressman Steven Derounian.

He served in the Nixon administration as the chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission from 1971 to 1973; this position led to his being called as a prosecution witness against former Attorney General John N. Mitchell and former Commerce Secretary Maurice Stans in an influence-peddling case stemming from international financier Robert Vesco’s $200,000 contribution to the Nixon reelection campaign.

He then served as Under Secretary of State for Economic Affairs (1973–1974) and chairman of the Export-Import Bank of the United States (1974–1976). During this era, he was also a member of the President’s Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board (1975–1976) and of counsel to Rogers & Wells (1976–1981).

With Antony Fisher, he co-founded the Manhattan Institute in 1978. He is the father-in-law of Owen Smith, Chairman of the Board of Trustees of the Institute of World Politics and Professor Emeritus at Long Island University.

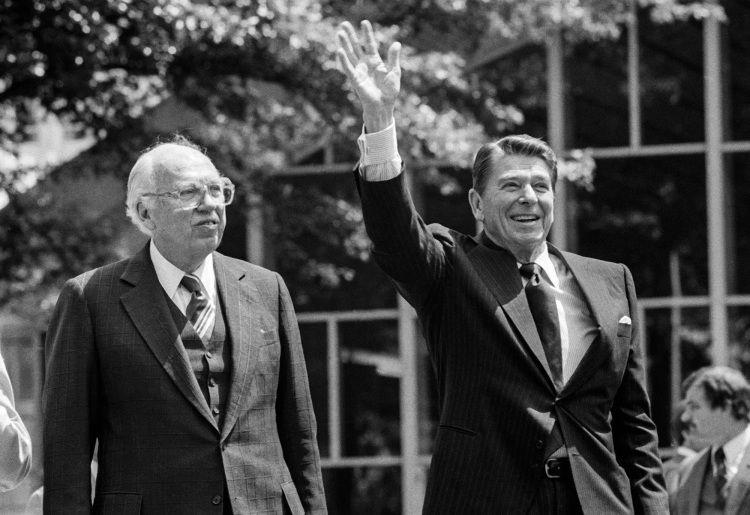

As campaign manager of Ronald Reagan’s successful presidential campaign in 1980, Casey helped to broker Reagan’s unlikely alliance with vice presidential nominee George H. W. Bush. He then served on the transition team following the election.

After Reagan took office, Reagan named Casey to the post of Director of Central Intelligence (DCI). Outgoing Director Stansfield Turner characterized the appointment as the “Resurrection of Wild Bill,” referring to Bill Donovan, the brilliant and eccentric head of Office of Strategic Services in World War II, whom Casey had known and greatly admired.

Despite Casey’s background in intelligence, the position was not his first choice; according to Rhoda Koenig, he only agreed to take the appointment after being assured that “he could have a hand in shaping foreign policy rather than simply reporting the data on which it was based.” Breaking precedent, Reagan elevated the role to a Cabinet-level position for the duration of Casey’s appointment.

Ronald Reagan used prominent Catholics in his government to brief Pope John Paul II of developments in the Cold War. Casey would fly secretly to Rome in a windowless C-141 black jet and “be taken undercover to the Vatican.”

Casey oversaw the re-expansion of the Intelligence Community to funding and human resource levels greater than those existing before the preceding Carter Administration; in particular, he increased levels within the CIA. During his tenure, post-Watergate and Church Committee restrictions were controversially lifted on the use of the CIA to directly and covertly influence the internal and foreign affairs of countries relevant to American policy.

This period of the Cold War saw an increase in the Agency’s global, anti-Soviet activities, which started under the Carter Doctrine in late 1980.

Casey was suspected, by some, of involvement with the controversial Iran-Contra affair, in which Reagan administration personnel secretly traded arms to the Islamic Republic of Iran, and secretly diverted some of the resulting income to aid the rebel Contras in Nicaragua, in violation of U.S. law. Casey was called to testify before Congress about his knowledge of the affair. On 15 December 1986, one day before Casey was scheduled to testify before Congress, Casey suffered two seizures and was hospitalized. Three days later, Casey underwent surgery for a previously undiagnosed brain tumor. While hospitalized, Casey died less than 24 hours after former colleague Richard Secord testified that Casey supported the illegal aiding of the Contras.

In his November, 1987 book, Veil: The Secret Wars of the CIA 1981–1987, Washington Post reporter and biographer Bob Woodward, who had interviewed Casey on a number of occasions for the biography, said that he had gained entry into Casey’s hospital room for a final, four-minute encounter—a claim which was met with disbelief in many quarters as well as an adamant denial from Casey’s wife, Sofia. According to Woodward, when Casey was asked if he knew about the diversion of funds to the Nicaraguan Contras, “His head jerked up hard. He stared, and finally nodded yes.”

In his final report (submitted in August 1993), Independent Counsel Lawrence E. Walsh indicated evidence of Casey’s involvement:

“There is evidence that Casey played a role as a Cabinet-level advocate both in setting up the covert network to resupply the contras during the Boland funding cut-off, and in promoting the secret arms sales to Iran in 1985 and 1986. In both instances, Casey was acting in furtherance of broad policies established by President Reagan.

There is evidence that Casey, working with two national security advisers to President Reagan during the period 1984 through 1986—Robert C. McFarlane and Vice Admiral John M. Poindexter—approved having these operations conducted out of the National Security Council staff with Lt. Col. Oliver L. North as the action officer, assisted by retired Air Force Maj. Gen. Richard V. Secord. And although Casey tried to insulate himself and the CIA from any illegal activities relating to the two secret operations … There is evidence that he was involved in at least some of those activities and may have attempted to keep them concealed from Congress.”

However, Walsh also wrote: “Independent Counsel obtained no documentary evidence showing Casey knew about or approved the diversion. The only direct testimony linking Casey to early knowledge of the diversion came from [Oliver] North.” Posthumously, the House October Surprise Task Force eventually exonerated Casey after first holding hearings to establish a need for investigation, the outcome of the investigation, the response of Casey’s family to the task force’s closure of the investigation, and Walsh’s final Independent Counsel report.

Casey was a member of the Knights of Malta. In 1948, he purchased Locust Knoll, an 8.2 acres North Shore estate centered around a main 1854 Jacobethan house in Roslyn Harbor, New York, for $50,000. After renaming the estate Mayknoll, it remained his principal residence until his death.

Casey died of a brain tumor on May 6, 1987, at the age of 74. His Requiem Mass was said by Fr. Daniel Fagan, then pastor of St. Mary’s Roman Catholic Church in Roslyn, New York, and his funeral was led by Bishop John R. McGann, who used his pulpit to castigate Casey for his ethics and actions in Nicaragua. It was attended by President Reagan and the First Lady. Casey is buried in the Cemetery of the Holy Rood in Westbury, New York.

He was survived by his wife, the former Sophia Kurz who died in 2000, and his daughter, Bernadette Casey Smith.

A lot happened in the year 1987, including the debut of a family-friendly TV sitcom set in San Francisco. The name of the show was Full House, and we’ll be doing a deep dive into this popular comedy over the coming weeks.

But first, to get a sense of the times and trends that helped shape this series, here’s a notable obituary from 1987 — Will Sampson.

Will Sampson was a Muscogee painter, actor, and rodeo performer. He is best known for his performance as the apparently deaf and mute Chief Bromden, the title role in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and as Crazy Horse in the 1977 western The White Buffalo, as well as his roles as Taylor in Poltergeist II: The Other Side and Ten Bears in 1976’s The Outlaw Josey Wales.

Sampson competed in rodeos for about 20 years. His specialty was bronco busting, and he was on the rodeo circuit when producers Saul Zaentz and Michael Douglas — of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest — were looking for a large Native American to play the role of Chief Bromden. Sampson stood an imposing 6’7″ (2.01 m) tall. Rodeo announcer Mel Lambert mentioned Sampson to them, and after lengthy efforts to find him, they hired him on the strength of an interview although had never acted before.

Sampson’s most notable roles were as Chief Bromden in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and as Taylor the Medicine Man in the horror film Poltergeist II. He had a recurring role on the TV series Vega$ as Harlon Two Leaf, and starred in the movies Fish Hawk, The Outlaw Josey Wales, and Orca. Sampson appeared in the production of Black Elk Speaks with the American Indian Theater Company in Tulsa, Oklahoma, where David Carradine and other Native American actors (such as Wes Studi and Randolph Mantooth) have appeared in stage productions. He also played Crazy Horse in The White Buffalo with Charles Bronson and the archetypal Elevator Attendant in Nicolas Roeg’s 1985 film, Insignificance. In 1980 Sampson was nominated for a Genie Award for “Best Performance by a Foreign Actor” for his role in Fish Hawk.

Sampson was a visual artist. His large painting depicting the Ribbon Dance of the Muscogee (Creek) is in the collection of the Creek Council House Museum in Okmulgee, Oklahoma. His artwork has been shown at the Gilcrease Museum and the Philbrook Museum of Art.

Sampson suffered from scleroderma, a chronic degenerative condition that affected his heart, lungs, and skin. During his lengthy illness, his weight fell from 260 lb (120 kg) to 140 lb (64 kg), causing complications related to malnutrition. After undergoing a heart and lung transplant at Houston Methodist Hospital in Houston, he died on June 3, 1987, of post-operative kidney failure. Sampson was 53 years old. Sampson was interred at Graves Creek Cemetery in Hitchita, Oklahoma. Will Sampson Road, in Okmulgee County (east of Highway 75 near Preston, Oklahoma), is named after him.

During the filming of The White Buffalo, Sampson halted production by refusing to act when he discovered that producers had hired white actors to portray Native Americans for the film. In 1983, with assistance from his personal secretary Zoe Escobar, Sampson founded the “American Indian Registry for the Performing Arts” for Native American actors. He also served on the registry’s Board of Directors. Sampson’s son Tim Sampson appeared on the FX Show It’s Always Sunny In Philadelphia Season 4 episode 10 titled “Sweet Dee Has A Heart Attack”. The episode pays homage to Will Sampson and his work as Chief Bromden in One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest. Tim Sampson plays “Tonto” after Frank (Danny DeVito) is mistaken as mentally incompetent and placed within a facility.